The third week of the workshop marks a shift in the kind of work we do. No longer are we exploring our abilities and interests through exercises and reading. Instead, with our target story and author techniques chosen, it is time to begin creating.

But just how do we start this new work? The writing week of the workshop, in which the participants will write their new plays to be performed, is often considered the most mysterious part of this process for those who have never been a part of it. And it’s easy to see why: writing is difficult, and it takes time. For many authors, they spend years looking at the blank page before finally managing to scribble down just a single sentence. But our young playwrights don’t have that kind of time.

Instead, starting the day after they have chosen the target story, the participants have exactly one week to produce a series of ten to fifteen-minute plays. It is challenging work. But it is also a testament to the workshop that every year these new pieces impress audiences with their gripping, hilarious, powerful, and intelligent writing.

For many authors, they spend years looking at the blank page before finally managing to scribble down just a single sentence. But our young playwrights don’t have that kind of time.

Which brings us back to how. I have visited the small groups at different times in their processes in order to represent how a piece goes from an idea to a fully fleshed out script, as well as how the writing process can differ depending on the writing techniques the group is influenced by. Hopefully, the process can be demystified, and you will be able to learn about what our participants are working on.

Starting writing week, the participants are given the text of the target story to work from at Sunday’s whole group session. Since this year’s target story is the short fairytale Rapunzel, the directors wanted to make sure the participants had plenty of text to work from, and so they were given multiple versions of the story.

Having a large amount of text to look over is important so that each of the groups has enough to pull from to make pieces that are different in focus. But a lot of text was also important for the writing of the first whole company piece under the influence of Grotowski. Emulating his technique of working directly with the text itself, the participants were given worksheets created by the directors that asked them to pull sentences directly from the story as well as manipulate some of the text. While the writing for the whole company pieces is usually anonymous, Grotowski’s actors spoke lines that resonated personally with them, and so our participants’ answers were recorded with their names.

Because there is not enough time and too many voices to have the participants take a thorough role in the creation of the whole company pieces, the directors assist the participants in creating them. With the fodder gathered from the worksheets, the directors will work together to produce and edit a script for the actors to perform—all of the lines being written by the actors themselves.

On Monday, the small groups begin to meet, now having time to have adequately read the target story, and discuss their ideas. I went to the Pinter small group to observe the start of their writing process.

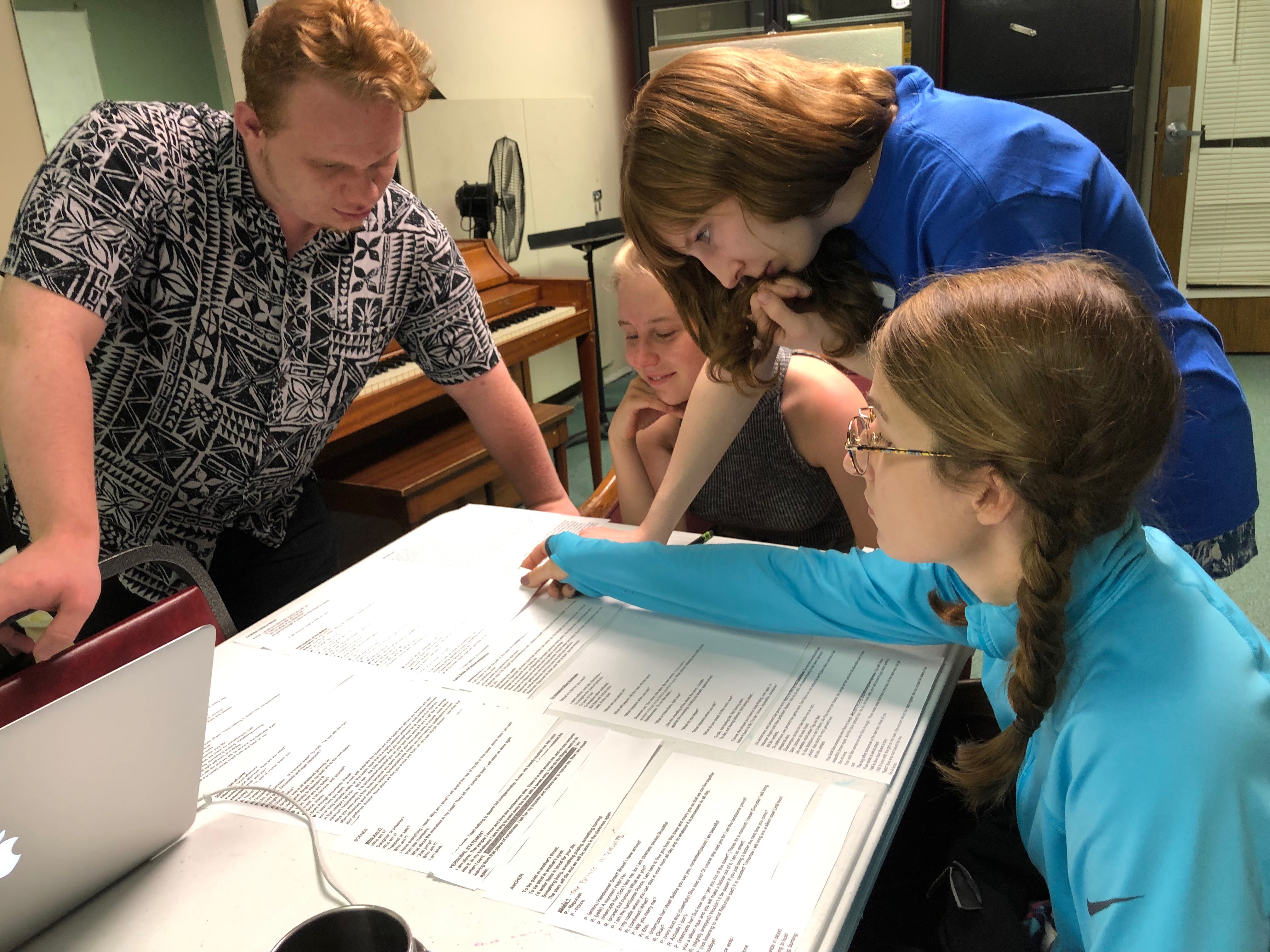

To begin, the participants reread the Pinter plays they were given. As the groups go about their writing, it is always important for them to continually review the plays they are working with in order to keep consistent with the techniques of the author. After reading Pinter’s works, the participants began to identify his techniques and devices that they need to work into their own play. For Pinter, he has differing techniques of writing with his memory plays and comedies of menace, and so the participants discussed the differences between each, as well as which ones they wanted to model their play after. Following a brief discussion, it was decided that they would write scenes that reflected both so they could fully explore the characters’ relationships in Rapunzel through Pinter’s lens of comedy and drama. The discussion about how and what to write can be a long one, and for many groups, it can take the entire first session. However, for the Pinter group, they were able to quickly identify some scenes they wanted to explore and what techniques to use in order to write them in.

Then the participants were given time to write. They typed and scribbled away, and when finished, they came back together to read what they had written. Everyone was a little hesitant at first, as it can be very vulnerable to share your work, but soon everyone was laughing and commenting on each other’s writing. One scene even gave me goosebumps. With the initial reading finished, an essential question is asked: What are we missing? The participants then came up with more ideas for scenes to write about. This is how the writing process will go for all of the groups—generating ideas, writing them, sharing with each other, and then generating new ones. For the end of the small group rehearsal, the participants were given homework to complete for the next session. When looking over what they had written, they realized it was still a ways from sounding like the techniques of Pinter. So, they each took a section of each other’s writing for editing more into the technique for next time.

Two days later, on Wednesday, I visited the Open Theater group during their second session to see what kind of material they were collecting for their piece.

The rehearsal started with them reading their writing to each other from the previous session’s homework. The play they are modeling their piece after, Terminal, focuses on the theater group’s individual responses to death. In the same fashion, our small group chose a theme they found in Rapunzel—the need for human connection—and devised scenes, found research, and wrote personal responses based off of it. During their discussion, they came up with ways to transform some of their writing, such as mixing their personal responses with text from the target story. Additionally, the directors led them in creating an “anchor” for their piece—a refrain to come back to after each section. Also, as Open Theater is all about collaboration, even in the staging of a piece, the group ended their rehearsal by creating some visual fodder of images and movement pieces that could go with their text.

Later that evening was our second whole company writing session. Our closing piece will be written with the techniques of Cocteau, and so Gwethalyn led the participants in an exercise to generate some writing. First, she asked them what they had not yet addressed in the story of Rapunzel in their small groups. Then, put into groups based off of the topics generated, the participants wrote stream-of-consciousness in the narrative technique of Cocteau for three minutes. When the time was up, they folded their pieces of paper over so that only the last line they wrote was showing, and then passed it to the next person. This way, the writers must now continue writing only with one line of context, and we are able to easily achieve Cocteau’s use of absurdity. Just like the Grotowski piece, this new writing will be edited down by the directors to make a script for the participants to perform.

Because the nature of our work is experimental, many rehearsal will begin like this—trying something multiple ways and deciding which one works best. Although it includes no text, it is its own form of writing.

Also at this rehearsal, we began exploring some rhythms for the opening piece. Grotowski’s works are highly rhythmic, and so, we began to try creating some soundscapes using shakers, tools, and our voices. Because the nature of our work is experimental, many rehearsals will begin like this—trying something multiple ways and deciding which one works best. Although it includes no text, it is its own form of writing. The participants sounded away as the directors listened and watched for what created the most dynamic look and sound. Here was one such experiment that included transitioning from shakers to vocalized syllables:

The next day, I caught back up with the Pinter group for their last writing session.

I was interested in hearing their scenes again, now that they had spent the week revising and editing them into a script that more resembled Pinter’s techniques. I was impressed with what I heard. Some of the scenes were completely different—the comedic ones were now full of fast-paced questions that menace just like Pinter’s works, and the ones modeled after his play Silence now felt even more ambiguous. They also completely changed the ending. During the course of the week, the participants’ writing is bound to transform, becoming more refined with each draft. All that was left for the small group was to edit their piece into a final script. But not all groups were as fast as this one.

When I returned to the Open Theater group on Friday, they were in the middle of creating more visuals for their piece.

They were busy working on a way for the three of them to move together, some of it inspired by climbing hair and some by walking blind. Also, they played some image theater with themes they picked out from Rapunzel. Using the exercises from the exploration phase of the workshop in our pieces is extremely common, as they look visually interesting, and the actors are ready to play with them in the context of their new pieces.

This was their last rehearsal before editing, so they returned to that familiar question: What are we missing? First, the group worked together to combine their writings to finish making the anchor for their piece. Also, after reviewing what they had written, one participant realized that they had only explored a darker view of what can happen when we are missing connection, but nothing about the joys of finally finding it. So, in the interest of fully representing all sides of their theme, they gave themselves the homework to write something exploring the benefits of connection. When they get together again, it will be time for them to take everything they wrote and start fitting it into a script.

The last group I had yet to observe was the Wellman small group. I sat in on their Saturday and Sunday rehearsals in order to watch their editing process.

By the end of writing week, most groups will have more writing than they can feasibly perform, and so cuts must be made. It can be a painful process, saying goodbye to something you wrote, but it always results in the best of the work being showcased. For a group using writing techniques that are more choral based, like Wellman, the amount of writing can be overwhelming. One participant remarked on the size of their writing as they were handed a printed version, “Oh, this is all one copy?”

To begin the editing process, they reread the Wellman play, reinforcing exactly what they were looking to keep in their own writing. Then the participants read everything they had written out loud. I laughed while listening to the familiar wordplay and educated absurdity that is undoubtedly Wellman. They also included their own entity known as Lacuna the translator (inspired by Wellman’s shriek operator in his play Antigone and the multiple translations of Rapunzel).

When finished, the group had about fifteen minutes worth of content. In order to get a manageable script size, they would have to cut it by at least a third. At first, the participants went through and highlighted only the sections they liked, but by the end, it still wasn’t enough. Next, they rearranged the remaining text into an order. To know what the flow of the piece will be like is helpful for knowing what to cut and keep.

Finally, the participants had to make some tough decisions. Whole sections were cut or reduced to just a few lines. It was also very tedious in other places:

“Should we cut the “the” there? “

“What if we kept only the last half of the sentence?”

“Wait, that line we cut should go back in here!”

By the end, the group’s script read around ten minutes—a little on the long side, but manageable. Victory! All that was left was to write a short ending using Wellman’s techniques in Antigone, and it felt appropriate that the group worked together to write it and reach the finish line. The feeling of having a completed script is elation like no other. You have worked hard over the past week to develop something to share with an audience. For the first time, you know what your piece is going to sound like. Now, it is time to decide what the piece is going to look like. And those decisions will be made over the next week during the staging process.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.